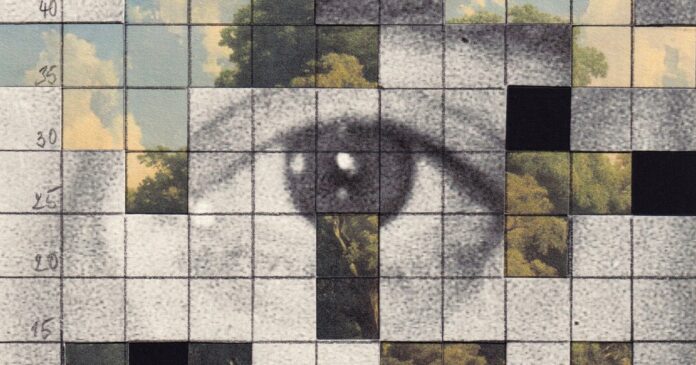

The narrative that our attention spans are collapsing under the weight of digital distraction is pervasive – and misleading. While many people feel more scattered, and data suggests declining focus in certain screen-based tasks, the framing of an “attention economy” being exploited misses the fundamental issue. The problem isn’t just that our attention is being stolen; it’s that we’ve reduced attention itself to a quantifiable, controllable commodity.

The Numbers Don’t Tell the Whole Story

Surveys show widespread concern: 75% of respondents report struggling with attention. Psychologist Gloria Mark’s research confirms a decline in sustained focus during digital activities, fueling the popular (though likely exaggerated) claim that human attention now lags behind a goldfish. Meanwhile, diagnoses of ADHD in children are rising, with roughly 11% of American kids now receiving this label.

These statistics are alarming, but they don’t necessarily prove a widespread cognitive failure. Instead, they reflect a shift in how we define and measure attention. The $7 trillion “attention economy” treats focus as a productivity metric, something to be optimized for profit. This narrow view then dominates even attempts to resist distraction – we become anxious self-accountants, desperately tracking our own focus instead of addressing the underlying issues.

Beyond Distraction: The Root of the Problem

The real crisis isn’t simply that phones, notifications, and endless content are pulling us in a million directions. It’s that we’ve internalized this transactional view of attention. The obsession with “improving focus” or “avoiding distraction” reinforces the idea that attention is a resource to be managed, rather than a fundamental aspect of being human.

This is especially dangerous because it ignores the broader context. Declining attention spans may be linked to systemic stress, economic insecurity, and the overwhelming complexity of modern life. Focusing solely on digital “fixes” ignores these deeper drivers.

A Call for Re-Evaluation

The anxiety surrounding the “attention economy” is itself a symptom of the problem. By fixating on how much attention we have instead of how we use it, we miss the bigger picture. Attention isn’t something to be hacked or optimized; it’s a capacity that flourishes in environments of meaning, purpose, and genuine connection.

The solution isn’t better self-discipline, but a fundamental re-evaluation of how we value and experience attention itself. We must move beyond the narrow metrics of productivity and reclaim attention as a source of human flourishing.